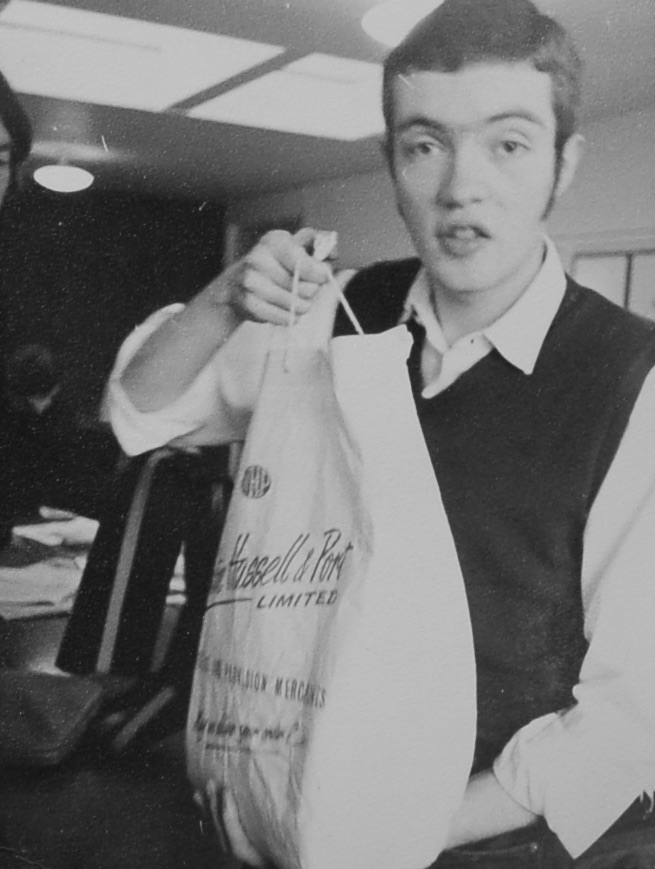

PAUL THOMPSON – The bloke least likely to

There’s an irony in the fact that I’m sitting writing this at my desk in the School of English Centre for Research Students, on the campus of the University of St Andrews, where I’m currently researching for a PhD. The irony is this:

Back in 1968/69 there was a saying in my cohort at Goldsmiths’ – you could hear it when exam results were posted – and it went “Oh, I did really badly in that exam. But at least I did better than Andy Clay and Paul Thompson!” Andy and I were two denizens of Raymont Hall. We would cruise in to college on his ratbike combination, he at the handlebars, I reclining in the sidecar with my Doc Martens up on the dashboard. We reckoned to look an incongruous pair, to make people do double-takes when they saw a greebo in a Biggles jacket and a skinhead in big boots on the saunter in New Cross. That was fun. But of all the people at Goldsmiths’, we were the two who didn’t really get why we were there. We did so many re-sits our behinds must have been permanently chair-shaped. They say if you can remember the 1960s you weren’t really there. Well, as it happens I canremember the sixties. I just can’t remember doing any work!

That situation came about thusly. I thought that when you wrote an essay at university, your tutor would be interested in what your actual opinions were, and if you had an original angle so much the better. So I turned in an essay for one particular German tutor; I was particularly proud of it because I felt it showed oodles of independent thought. I got a miserable mark for it. “Okay,” I said to myself, “they don’t want independent thought at all.” So for my next essay, I just reproduced what the tutor had said in the previous seminar. We had been discussing Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, and he had made a point of talking about the irony of Gustav von Aschenbach’s vaunted “virginal manliness” being overturned by a sudden passion for an adolescent boy. So in my next essay I talked about the irony of von Aschenbach’s virginal manliness being overturned by a passion for an adolescent boy. I got another miserable mark. The tutor called me into his office to discuss my performance.

“Have you got something against homosexuals?” he asked.

“No,” I said, puzzled.

“Then why all this about von Aschenbach’s virginal manliness being overturned by a passion for an adolescent boy?”

“Because that’s what you said.”

“No it isn’t!”

“Yes it is!”

“No it isn’t!”

That’s the moment at which I gave up. If they did not want independent thought, and they didn’t want to see their own ideas reproduced, what didthese tutors want? I came to the conclusion that it just wasn’t worth working. From then on I dodged lectures, tutorials, seminars. I failed exams, and used whatever information I could gather from them to cram a bit of knowledge to scrape through the re-sits. I became the bloke least likely to get a degree, and in the end, I didn’t. By the end of 1969 I had a severe health problem, and in early 1970 the then Dean of Studies told me to take a year out to get my health back, and then come back. I took the year out, but didn’t come back.

And yet, being at Goldsmiths’ was one of the best times of my life! Despite not working, despite preferring to date working-class girls I met at the Savoy Rooms in Catford (where they played really boss Reggae) rather than young women from my cohort, despite often dreading going in to college in the morning, there was so much that I look back to, fifty years on, and think, “My stars – that was bloody great!” For a start, the politics of the late sixties, as manifested in the Goldsmiths’ microcosm, was vibrant and dynamic. We had every shade of leftist: Trotskyists, pro-Moscow Communists, Anarchists (I was one of those), “big tent” Communists, Situationists, Marxist-Leninists, you name it. The Marxist-Leninists even went around in olive drab Mao suits and caps with a red star on them. One of the nicest Communists, Bob Portway an ex-mod, gave me two mohair suits that were no longer his style. Cool! There was so much bickering and name-calling between the various leftists, however, that I sometimes went drinking with the chairman and treasurer of the Conservative Society, because at least we could have a decent conversation about football. The friends I made were an unpredictably motley bunch. One of them went on to manage the Sex Pistols. Another one, having a bad time, said to me “We minorities need to stick together – blacks and skinheads – we need to stick together.” Damn right, bro.

Oh yes, the skinhead thing. It was just a thing, nothing more. It had to do with the duds I liked to wear and the music I liked to listen to and the places I liked to hang out. It had to do with the London street fashion of the time – Ivy League but with a Cockney swagger, and sometimes with boots. It passed by without too much notice at Goldsmiths’, where no more than half a dozen people had this style, except we were considered a little weird for not having long hair. Then the Observer colour magazine ran a piece about the Smithies, a bunch of working-class lads from Deptford, and suddenly people were calling out “Hey, Smiffie!” at me and my mate Mark Cullinan as we walked down the corridor. Mind you, this did lead to a forgotten moment in Rock history. So much had the audience at the Free Festival in ’69 enjoyed the band Ambrose Slade, that the Social Secretary of the Student Union booked them for a return gig. I happened to be on the saunter through the Union offices at the moment that they arrived for the gig, and was surprised to find that they had all affected short hair and a rather inaccurate pastiche of skinhead clobber – Tesco Bomber jeans, hobnail boots, button-braces worn with belts, and other horrors. So right then and there I gave them a run-down of what they had got wrong, and told them what they needed to get right. So if anyone wants to know who gave Slade (for it was they!) their classic skinhead look, it was I.

Oh, Rock history. At that time Goldsmiths’ SU was going through a run of superb Social Secretaries, who booked the most brilliant bands. One solid coup was managing to get blues legend Muddy Waters to come and play for us. I was seconded to security for the night, and my ‘beat’ was the dressing rooms – actually the Student Union offices. The whole thing was really relaxed. Everybody sat round a table, and I got to sit next to Muddy Waters! British bluesman Alexis Korner turned up with his children, all with flowing blond locks and immaculate Afghan coats, and they called the great man “Uncle Muddy,” which he tolerated with a smile. Back in the USA, of course, “Uncle” would have been an insult. Support artist Gordon Smith started playing “I Can’t Be Satisfied” on his guitar, and Muddy started singing it. At one point, Muddy turned to me and said, “That poster they’ve put up… that picture’s not me, it’s John Lee Hooker.” He was dead right. I said something crass in reply, and then wanted the ground to swallow me. But – hey! – I got to sit next to Muddy Waters.

So this was the golden stuff, the dream stuff. There was bad stuff for me too, but Goldsmiths’ still counts me as an alumnus and sends regular mailshots. I didn’t get my degree, I didn’t come back after a year out, I went into a boring job instead. When I retired, I re-kickstarted my education, got a 1st Class BA Honours in English Lit from the OU, went on to get an MSc with Distinction in Literature and Modernity from the University of Edinburgh, and am currently bucking for a Doctorate, as I said, at St Andrews. This is ‘the bloke least likely to’ speaking. This is the bloke who everybody was glad they did better than. Funny old world.

I wonder what became of Andy Clay. I’d really like to know.

Paul Thompson